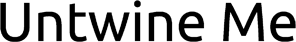

Not strictly a film but a play written for television, Made in Britain follows the riotous exploits of a 16 year-old Neo-Nazi skinhead named Trevor, whose most distinguishing feature is a swastika tattooed between his eyes à la Charles Manson. Trevor is an archetypal angry young man. He’s fierce but intelligent, obnoxious yet lonely. When we begin Trevor has just been sent to a youth rehabilitation center for several weeks where psychiatrists and other professionals will assess his behavior. Despite the fact that Harry, his social worker, tells him that this is his last chance to get on the straight and narrow before prison Trevor continues to disregard all forms of authority and in the the end sucks poor Errol, his meek and illiterate roommate, into his vortex of vandalism.

Trevor is highly intelligent but sees himself as the victim of an authoritarian system but he is convinced he can beat the system using violence, vandalism and defiant rhetoric. Being so intelligent and articulate only makes it harder and more frustrating for those who genuinely try to help him like his long-suffering social worker Harry or the Superintendent of the rehabilitation home who chalks out on the blackboard the vicious circle Trevor is in danger of stepping in to if he doesn’t seize on this last chance. If he can’t sort himself out here, he will end up in borstal and thereafter prison. All too often Trevor is too angry to care about being helped. In the two or three days the film covers Trevor steals several vehicles, sniffs glue, smashes the windows of a business and multiple private residences, assaults the rehab center’s cook, kicks in a door, crashes a Transit van into a police car outside a police station, urinates on his own case files while having meek Errol defecate on his, and there’s more that I’m probably forgetting… not to mention Trevor’s verbal defiance of every single authority figure from doctor to judge to police officers with copious use of that great British perjorative, Wanker!

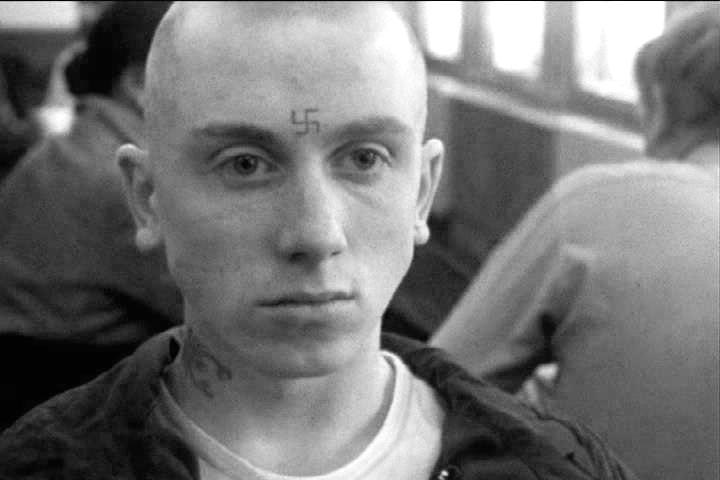

Throughout the film we are persistently in or around dilapidated buildings and institutional locations creating an atmosphere not only of Thatcherite society in decay (the teleplay aired in 1982) but also the moral and spiritual decay of an angry working class embodied by Trevor. And the real reason to watch Made in Britain is to witness Tim Roth’s Trevor whose seething performance is both astounding for its rabid ferocity and repulsive for his unapologetic torrents of racist vitriol. But, as is the case with many angry young men, behind Trevor’s aggressive façade is a desperate and lonely individual so doomed to fail it is hard not to pity him.

–Zachariah Rush

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Zachariah Rush was born in Manchester, England where his early poetry was published in small press anthologies and journals. Since moving to the USA in 2007 he has published the books ‘Beyond the Screenplay: A Dialectical Approach to Dramaturgy’ (McFarland, 2012) and ‘Cinema & its Discontents’ (McFarland, 2016), as well as dozens of essays of film criticism in journals published by Intellect (UK) and University of Chicago Press (USA). He also translated Albert Camus’s existential classic L’étranger into a libretto for operatic performance. His most recent publication was the autobiographical poem ‘Ode to Bipolar’ published in Poetry Now the journal of the Sacramento Poetry Center.