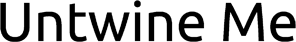

L’Étranger (The Stranger) by Albert Camus is undoubtedly one of the most iconic philosophical works in the human history. Published in English as The Outsider, this is among Camus’ best works along with other masterpieces like the The Plague and The Fall.

Based on the Camus’ philosophy and the theme of absurdism, this 1942 novella revolves around the life of Mersault, an apathetic French settler in Algeria who brutally murders an Arab man, a day after his mother’s funeral. He is tried and sentenced to death. The story is divided into two parts from a first-person narrative with his views on life and its components before and after the murder.

In January 1955, Camus wrote this:

I summarized The Stranger a long time ago, with a remark I admit was highly paradoxical: “In our society any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.”

I only meant that the hero of my book is condemned because he does not play the game.

In 1957, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature “for his important literary production, which with clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in our times.”

Let’s take a look ten of the most hard-hitting quotes from The Stranger:

I opened myself to the gentle indifference of the world.

I looked up at the mass of signs and stars in the night sky and laid myself open for the first time to the benign indifference of the world.

It was as if that great rush of anger had washed me clean, emptied me of hope, and, gazing up at the dark sky spangled with its signs and stars, for the first time, the first, I laid my heart open to the benign indifference of the universe.

To feel it so like myself, indeed, so brotherly, made me realize that I’d been happy, and that I was happy still. For all to be accomplished, for me to feel less lonely, all that remained to hope was that on the day of my execution there should be a huge crowd of spectators and that they should greet me with howls of execration.

Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can’t be sure.

It is better to burn than to disappear.

Nothing, nothing mattered, and I knew why. So did he. Throughout the whole absurd life I’d lived, a dark wind had been rising toward me from somewhere deep in my future, across years that were still to come, and as it passed, this wind leveled whatever was offered to me at the time, in years no more real than the ones I was living. What did other people’s deaths or a mother’s love matter to me; what did his God or the lives people choose or the fate they think they elect matter to me when we’re all elected by the same fate, me and billions of privileged people like him who also called themselves my brothers? Couldn’t he see, couldn’t he see that? Everybody was privileged. There were only privileged people. The others would all be condemned one day. And he would be condemned, too.

Mother used to say that however miserable one is, there’s always something to be thankful for. And each morning, when the sky brightened and light began to flood my cell, I agreed with her.

At that time, I often thought that if I had had to live in the trunk of a dead tree, with nothing to do but look up at the sky flowing overhead, little by little I would have gotten used to it.

I felt that I had been happy and that I was happy again. For everything to be consummated, for me to feel less alone, I had only to wish that there be a large crowd of spectators the day of my execution and that they greet me with cries of hate.

“Have you no hope at all? And do you really live with the thought that when you die, you die, and nothing remains?” “Yes,” I said.”

Written by Sparsh Paul